RPCs¶

iTerm2 offers a very powerful facility where a script (typically a daemon) registers a function as available to be invoked by iTerm2.

For example, suppose you want to bind a keystroke to clear all history in all sessions.

This script shows a working example:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import iterm2

async def main(connection):

app = await iterm2.async_get_app(connection)

@iterm2.RPC

async def clear_all_sessions():

code = b'\x1b' + b']1337;ClearScrollback' + b'\x07'

for window in app.windows:

for tab in window.tabs:

for session in tab.sessions:

await session.async_inject(code)

await clear_all_sessions.async_register(connection)

iterm2.run_forever(main)

A lot of this should look familiar from the Daemons example. Let’s focus on the parts we haven’t seen before.

This call defines the RPC:

@iterm2.RPC

async def clear_all_sessions():

This function definition is modified by the @iterm2.RPC decorator. It adds a register value to the function which is a coroutine that registers the function as an RPC. Here’s how you call it:

await clear_all_sessions.async_register(connection)

This exploits a quirk of Python that functions are capable of having values attached to them in this way.

Registered RPCs like this one exist in a single global name space. An RPC is identified by the combination of its name (clear_all_sessions, in thise case) and its arguments’ names, ignoring their order. Keep this in mind to avoid naming conflicts. Python’s reflection features are used to determine the function’s name and argument names.

Your RPC may need information about the context in which it is run. For example, knowing the unique identifier of the session in which a key was pressed that invoked the RPC would allow you to perform actions on that session.

Your RPC may take a special kind of default parameter value that gets filled in with the value of a variable at the time of invocation. Suppose you want to get the session ID in which an RPC was invoked. You could register it this way:

@iterm2.RPC

async def clear_session(session_id=iterm2.Reference("id")):

code = b'\x1b' + b']1337;ClearScrollback' + b'\x07'

session = app.get_session_by_id(session_id)

if session:

await session.async_inject(code)

await clear_session.async_register(connection)

The function invocation will not be made if the variable is undefined. If you’d prefer a value of None instead in such a case, use a question mark to indicate an optional value, like this: Reference(“id?”).

The “id” is a variable that exists in the session’s scope. To learn more about how variables work and which variables are defined, see Scripting Fundamentals

Invocation¶

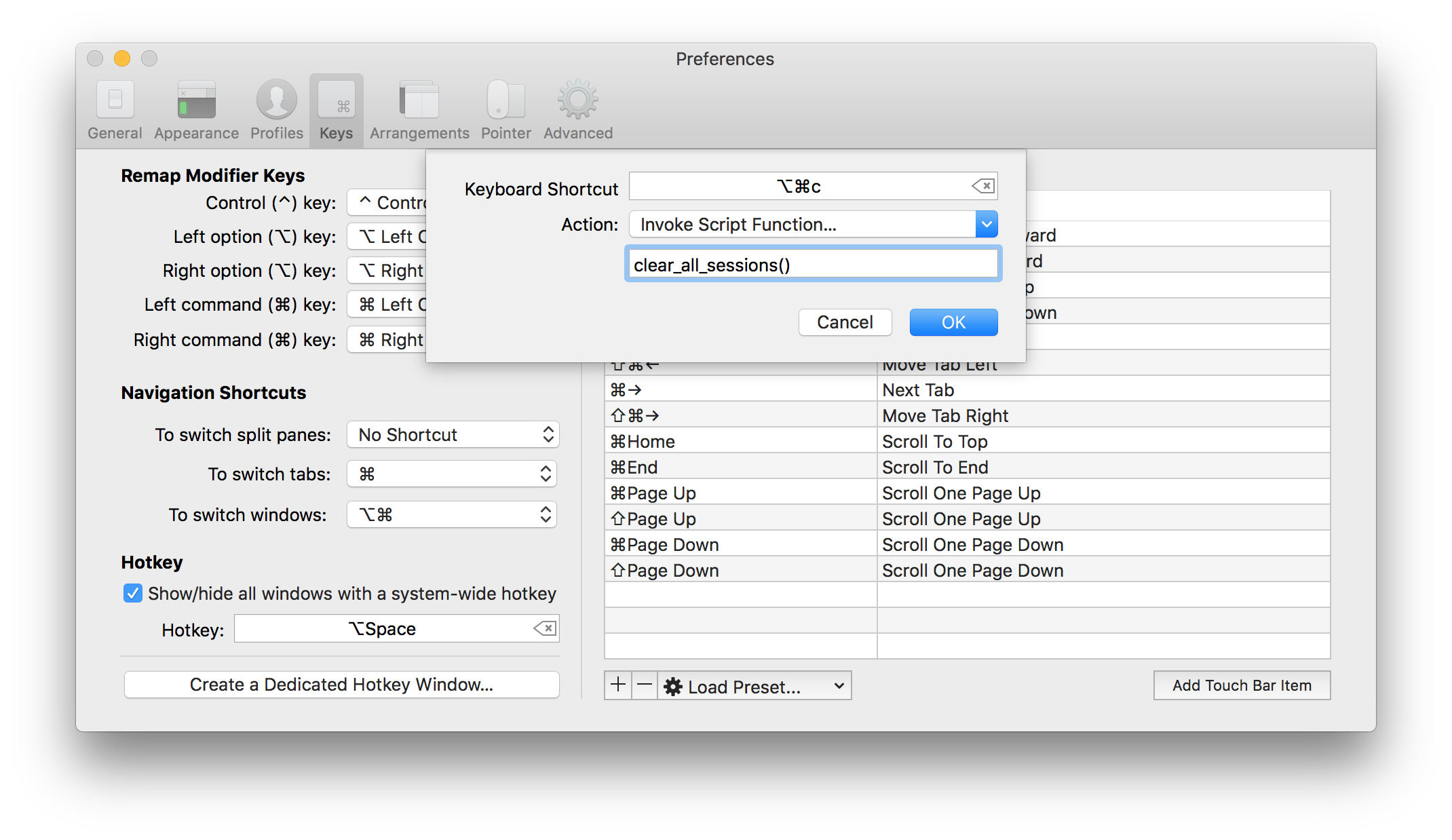

To invoke an RPC, create a key binding for it. Go to Preferences > Keys and click the + button. Select Invoke Script Function as the action and enter a function call in the field beneath it. Like this:

Then press the associated keystroke and the function will be invoked.

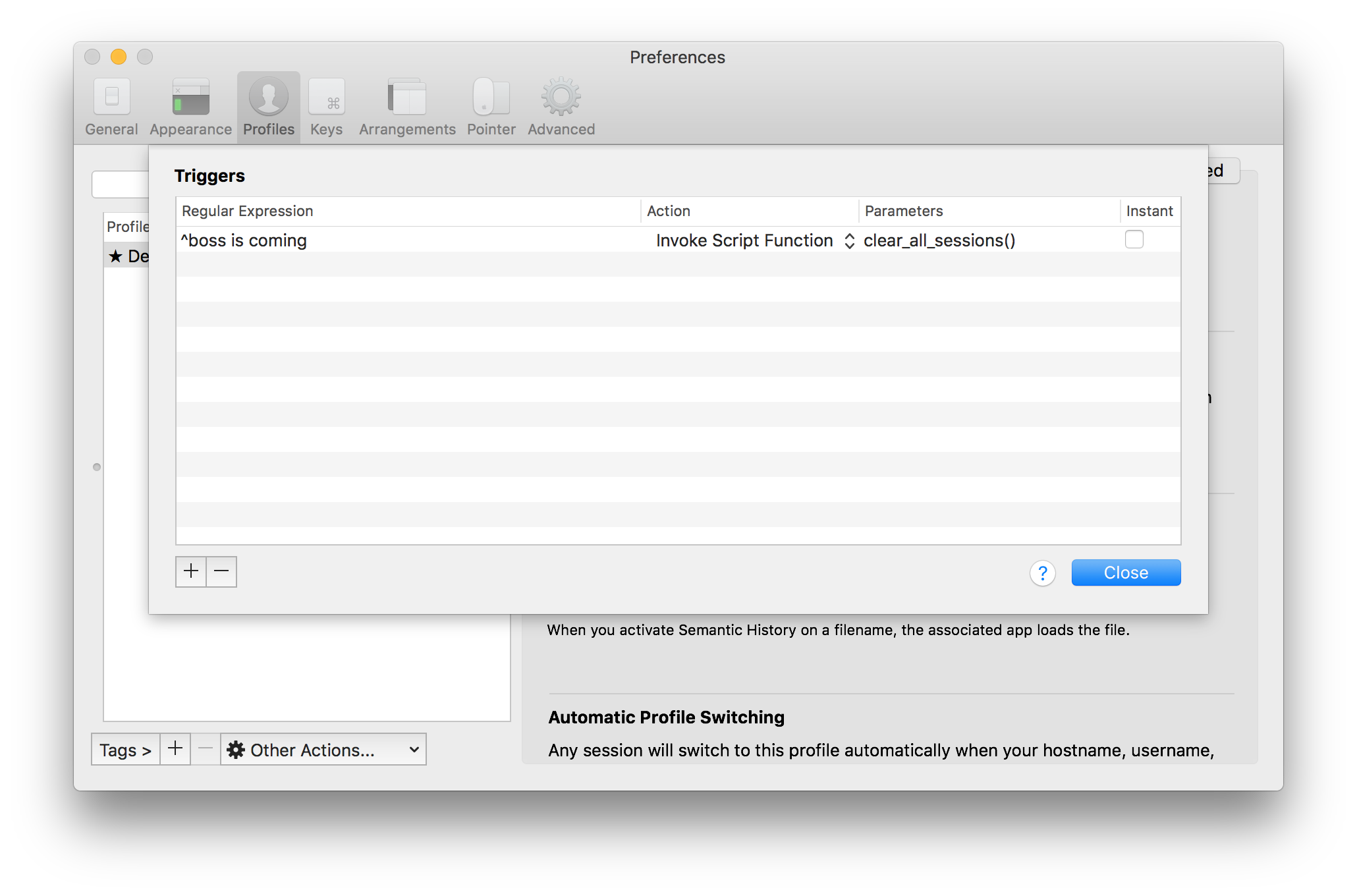

You can also bind a trigger to invoke a function automatically:

REPL¶

You can test RPCs defined in the REPL. First, define them as usual. When the RPC gets invoked, the REPL must allow the event loop to run so it can handle the request from iTerm2. The simplest way is to tell it to watch for requests for a set period of time, like this:

await app.connection.async_dispatch_for_duration(1)

The argument of 1 is how long to wait in seconds. Requests to execute registered functions wait in a queue until they can be handled. That means you can press a key in iTerm2 to invoke the RPC and then do async_dispatch_for_duration(0.1) and it will be handled immediately.

Arguments¶

Registered RPCs may take arguments. Any argument may take a value of of None, so take care to handle that possibility.

When an RPC is invoked, it uses a slightly different syntax than Python. That’s because iTerm2’s scripting interface is meant to be language-agnostic (although at the time of writing there are only Python bindings).

Here’s what a function invocation might look like:

my_function_name(session: id, favorite_number: 123, nickname: "Joe")

The name of the function and the name of each argument is an Identifier. Identifiers begin with a letter and may contain letters, numbers, and underscore. Every character must be ASCII.

Each argument must have a distinct name.

The value passed to an argument must be an expression. The most common types of expressions are:

A variable reference, like id.

A variable is a named piece of data attached to a session, tab, window, or the iTerm2 application itself. Some are defined by iTerm2, like id, which takes a string value that uniquely identifies a session. Others, beginning with user. may be defined by the user.

For a full list of the iTerm2-defined variables, see Variables.

To set a user-defined variable, you can use a control sequence or call

iterm2.Session.async_set_variable(). Variables can take any type JSON can

describe.

A reference to an unset variable raises an error, preventing the function call from being made. If you modify the path to end with ? that signals it is optional. Optional variables, when unset, are passed as None to the Python function.

If a terminal session does not have keyboard focus then no session. variables will be available.

A number, like 123.

Numbers are integers or floating point numbers. They can be negative, and you can use scientific notation.

A string, like “Joe”.

Strings are escaped like JSON, using backslash. Strings may contain embedded expressions. For more information on this, see the Interpolated Strings section of Scripting Fundamentals.

The result of a function call.

For more details, see Composition.

Scripting Fundamentals goes in to more detail on expressions.

Timeouts¶

By default, iTerm2 stops waiting for a function’s result after five seconds. The function continues to run until completion. You can pass an optional timeout parameter to async_register to set your own timeout value in seconds.

Composition¶

Function invocations may use composition. A registered function can return a value which the becomes an argument to a subsequent function call. Here’s a snippet of an example, which you can add to the main function of the previous example:

@iterm2.RPC

async def add(a, b):

return a + b

await add.async_register(connection)

@iterm2.RPC

async def times(a, b):

return a * b

await times.async_register(connection)

@iterm2.RPC

async def show(s):

session = app.current_window.current_tab.current_session

await session.async_inject(bytes(str(s), encoding="utf-8"))

await show.async_register(connection)

To compute 1+2*3 and inject it into the current session, use this invocation:

show(s: add(a: 1, b: times(a: 2, b: 3)))

Note that if there are invocations that have no dependencies, they may run concurrently. There is no guarantee on the order of invocations except that an RPC will not be made until all its dependencies have completed without errors.

Errors are propagated up the call chain and shown in an alert with a traceback.

Continue to the next section, Hooks.