Scripting Fundamentals

Introduction

Sessions, tabs, windows, and the iTerm2 application itself each have bits of information that are useful to users and script writers. For example: a session has a working directory, a tab or a window may have a custom title, and the iTerm2 process has a theme such as light or dark mode.

iTerm2 manages the storage and communication of this information with a system called "variables".

A variable exists in some context. Each session, tab, and window has its own context. The application itself also has a context, called the global context.

A variable has a name, such as hostname, and a value. The value is any data

type encodable in JSON: numbers, booleans, strings, dictionaries, arrays, and

null. There is also a special kind of variable that references a different

context, allowing you to reach (for example) variables in the tab's context

from its sessions' contexts.

iTerm2 defines a number of built-in variables. There are also special contexts for user-defined variables. A user-defined variable has a value set by a control sequence or a script.

Variables were originally invented for Badges as a way for users to embed text in a badge. For example, a shell script could set a user-defined variable containing the name of the current git branch, and that could be displayed in the badge.

As the Python scripting API was developed, it became clear that variables were a useful tool for sharing information between iTerm2 and scripts.

See the Variables Reference for information about built-in variables.

Continue reading to see how variables can be used.

Function Calls

Scripts may register functions which users can invoke through various hooks. For example, you can bind the invocation of function call to a keypress or a trigger.

An invocation names the function, its arguments, and the values being passed to the function.

For example, let us consider a hypothetical function that creates a new window

using a passed-in initial working directory and profile. We'll name our

function create_window, since every function has a name.

A function may take parameters, and every parameter has a name. Let's call the

parameter names for our example initialDirectory and profileName.

To open a window with the initial working directory of /etc and profile

Default we would use the following invocation syntax:

create_window(initialDirectory: "/etc", profileName: "Default")

Because every parameter is named the order of parameters does not matter. You could exchange them and it would work the same.

If you wanted to use the working directory of the user's current session and you knew the function would be invoked in the session context (which is the context in which almost all function invocations occur) you could write:

create_window(initialDirectory: path, profileName: "Default")

The identifier path refers to a variable in the session context which holds

the user's current working directory.

A function may also return a value. That will be discussed in the section on interpolated strings below.

To learn how to write your own functions, follow the Python Scripting Tutorial.

Built-in Functions

iTerm2 provides a few built-in functions. There are not many because this is a relatively new feature and is still under development.

iterm2.alert(title: str, subtitle: str, buttons: [str, ...])- Shows a modal alert. If the buttons array is empty, OK will be shown.iterm2.count(array: [Any])- Returns number of items in the array.iterm2.get_string(title: str, subtitle: str, placeholder: str, defaultValue: str, window_id: str?)- Prompts the user for textual input.iterm2.move_tab_to_window(tab_id: str)- Moves the tab into its own window.

Expressions

The preceding discussion of function calls showed how you can pass strings or paths to variables as arguments. The following types of expressions are supported:

- Interpolated strings

- Integers

- Floating point

- Array literals

- Array dereferences

- Function calls

- Paths to variables

Interpolated Strings

These are described below.

Integers

These are decimal integer literals. For example, -3, 0, and 2.

Floating point

Floating point values look like -1.2, 0, 2.3, or 1.2e5.

Array Literals

Array literals are of the form:

[ expression, expression, ... ]

They may contain zero or more expressions.

Array dereferences

Array dereferences are of the form:

path[index]

Where path is the path to a variable and index is a number. Yes, this is a

very restrictive syntax! It is there for a very specific purpose (the matches

array passed to Triggers' interpolated strings) and will be expanded in the

future, if needed.

Function calls

A function call, as described above (e.g., foo(bar: baz)) is an expression.

This implies that function calls may be composed.

Paths to variables

Variables in the current context can be referred to by a path like jobName,

but you can also specify multi-part paths that refer to variables in different

contexts. See the section Following Context References, below.

Interpolated Strings

Another way that variables are exposed in iTerm2's user interface is through interpolated strings. An interpolated string is a string of text that contains embedded function calls or references to variables.

iTerm2 borrows some of the Swift language's syntax for interpolated strings.

This is not an attempt to implement the full Swift language, nor will iTerm2

ever contain a full-fledged language of its own. To embed an expression in a

string, place it in \(…). For example, you could set a session's name to:

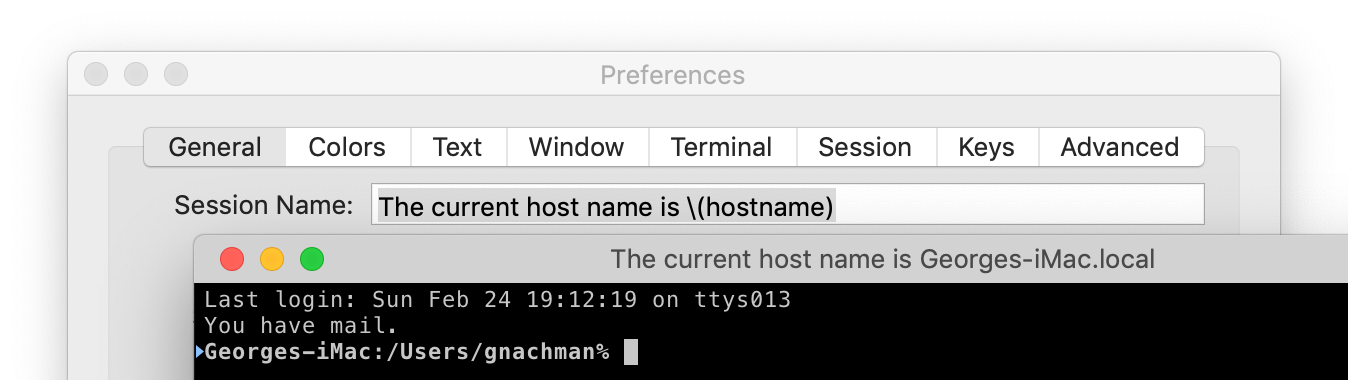

The current host name is \(hostname)

The expression hostname will be replaced with its value. Since hostname is

a variable defined in the session context, and iTerm2 defines it to be the name

of the current hostname, the session's name will appear as something like

The current host name is example.com.

Here's an example showing the interpolated string in the preferences window and the resulting session title:

As a function call is a valid expression, these may also go in interpolated strings. The function's return value will be converted to a string and expanded just as an expression referencing a variable is replaced with the variable's value.

For example, suppose you have a function add(x,y) that adds two numbers.

Let's set the session name to:

Two plus three is \(add(x: 2, y: 3))

The session's name as it appears in the tab bar would be Two plus three is 5.

Interpolated strings may be nested. For example, imagine a function cat(x,y)

that concatenates the value of x with the value of y. This would be a legal

interpolated string:

\(cat(x: "Lorem \(cat(x: "ipsum ", y: "dolor")) sit ", y: "amet"))

Its value would be Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.

Contexts

When writing an interpolated string, you must be mindful of the context in which

it is evaluated. For example, window titles are evaluated in the window's context.

If you want to put the current session's hostname in the window title, you'd use

\(currentTab.currentSession.hostname). Likewise, tab titles are evaluated in

the tab's context.

Following Context References

Some variables reference another context. For example, the session context has

a variable named tab that references the session's containing tab's context.

Likewise, the tab context has a currentSession variable that references the

current session's context.

You can chain variable references with .. For example, the working directory

of the current session of the containing tab is given by:

tab.currentSession.path

Setting User-Defined Variables

You can set user-defined variables that are attached to a session. These always

begin with user.. For example, user.gitBranch.

Shell Integration

The easiest way to set a user-defined variable is with shell integration. Modify your shell's rc script by defining a function named iterm2_print_user_vars that calls iterm2_set_user_var one or more times.

Here's an example that sets a user-defined variable called "gitBranch" to the git branch of the current directory. Pick your shell to see the version you need:

# bash: Place this in .bashrc.

function iterm2_print_user_vars() {

iterm2_set_user_var gitBranch $((git branch 2> /dev/null) | grep \* | cut -c3-)

}

You could then set your badge to \(user.gitBranch), for example.

Control Sequence

User-defined variables may be set with the following escape sequence:

OSC 1337 ; SetUserVar=name=Base64-encoded value ST

Here's a shell command that demonstrates setting user.foo to the value bar:

printf "\033]1337;SetUserVar=%s=%s\007" foo `echo -n bar | base64`

This is what iterm2_set_user_var sends. Generally you should use the iterm2_print_user_vars mechanism described above instead of sending this escape sequence directly.

Python Script

Use Session.async_set_variable()

in a Python script to set a user-defined variable.